A view of the U.S. Capitol dome's ceiling

Cross-cutting

Policy

When the first modern electric cars hit the market in the late 1990s , interest was limited. The first people to buy them were either very rich, very climate-conscious, or both.

It wasn’t until the 2010s that electric vehicles (EVs) finally found something like a mass market. Why? Batteries became much cheaper, and EVs became far more affordable — but another key factor was that the government intervened. In 2009, the United States implemented a federal EV tax credit, giving a $7,500 rebate to anyone who purchased a qualifying EV. One 2018 study found that every $1,000 offered as a rebate or tax credit increases average sales of EVs by 2.6%.

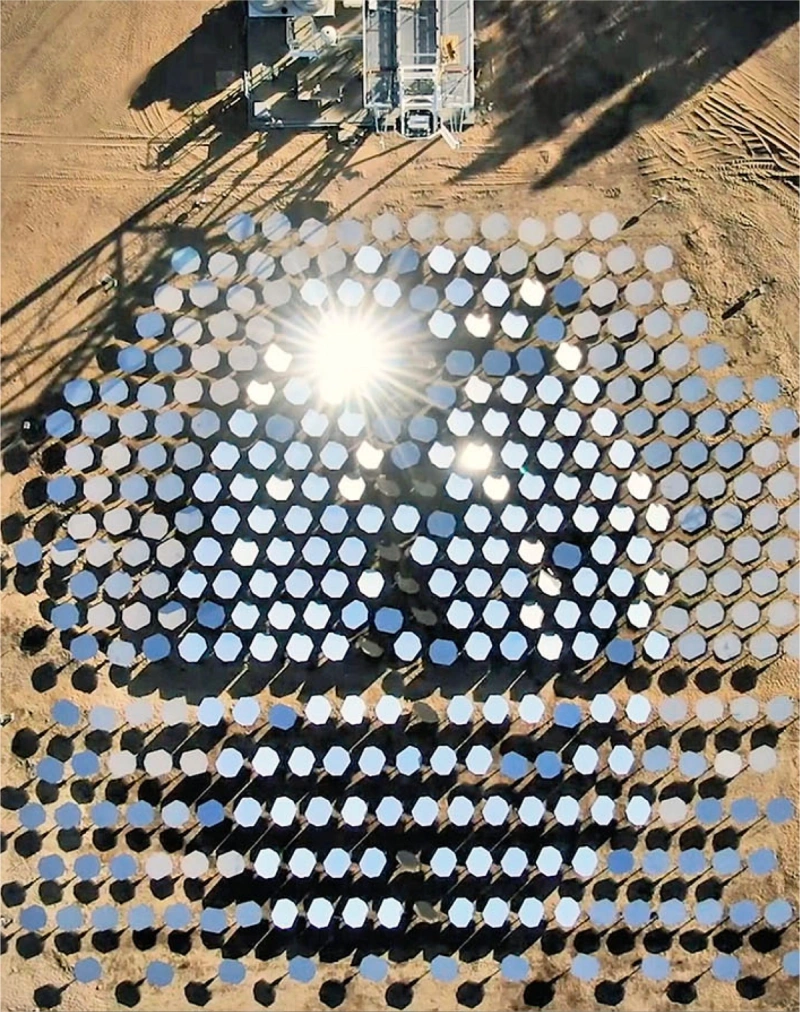

Startup Heliogen uses fields of AI-controlled mirrors to harness the power of the sun.

This is the perfect example of why climate innovation doesn’t happen in a vacuum: technology is important, but policy is often what moves the needle on adopting them at scale.

Even if new green technologies are perfect — which the first electric cars certainly weren’t — they have their limits. The fundamental challenge of inventing zero-carbon products, from electric vehicles to green cement to sustainable jet fuel, is that there’s no natural market for them. Sure, you might get a few wealthy climate advocates to buy them, but without some extra incentive, they won’t catch on.

That’s why the people historically tasked with fixing broken markets — policymakers — are as important as innovators and scientists in achieving a zero-carbon world .

Cross-cutting

At Breakthrough Energy, we support this policy-making around the world, drawing on our technical expertise across all the different sectors you just read about.

Of course, every country’s journey to net zero will be different, and so will the policies they need. But at the highest level, when we think about climate policy from a global perspective, it can be divided into three parts.

The first is the highly-industrialized, high-income countries , like the U.S. and many European countries, where a lot of innovation is happening, and where governments are wealthy enough to help fund the transition to lower sources.

Then there are the middle-income countries — like Brazil, India, and China — who often have higher real-time emissions, but are also the largest markets for adopting those technologies.

Finally, there are low-income nations across the Global South , which don’t have the money to pay for these things, but still need them — arguably the most — because their populations are the most vulnerable to extreme climate change.

United States

The United States is the second-largest greenhouse gas (GHG) emitter in the world.

1

1

As the United States moves to meet its climate goal of reducing emissions by 50% in 2030, it can simultaneously inspire and incentivize the energy transition in the rest of the world.

USPA Vice President Aliya Haq on stage with presidential advisor John Podesta

First, the good news

American climate policy in recent years has been a rare bright spot in our field. The Energy Act of 2020, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law of 2021, the CHIPS and Science Act of 2022 (CHIPS), and the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 (IRA) — all signed into law, three of them with bipartisan support — will help reduce U.S. emissions and drive down green premiums for emerging clean technologies.

Together, these bills will invest at least $500 billion in clean energy — with the potential for the total investment over 10 years to climb to over one trillion, depending on how much demand is created in the private sector.

But much more work remains to ensure that these laws are implemented successfully, as well as to ensure progress in future climate policy. Our U.S. Policy & Advocacy Team aims to cut through it by leveraging our in-house team of experts, our uniquely strong network, partnerships forged through grantmaking, and a longer-term view than workaday politics can often afford.

Looking to 2024 and beyond, our policy team is focusing on multiple fronts . We’re helping agencies implement new funding and tax credits , advocating for more long-distance transmission lines to accommodate increased electrification, focusing policy work on “hard to abate” sectors like agriculture and aviation, and driving the conversation forward around technology-neutral performance standards for electricity, fuels, and manufactured products — to name just a few tracks in which we work.

Cross-cutting

Europe & the

United Kingdom

2

2

In 2019, the United Kingdom (UK) became the first G7 economy to commit by law to net zero by 2050. Soon after that, the European Union (EU) became the world’s first multinational bloc to set a legally binding net-zero emissions target, dubbed “Fit for 55,” referring to its 2030 target of reducing emissions by 55% (compared to 1990 levels), through reforms covering everything from renewable energy and energy efficiency to green hydrogen mandates.

A geothermal power station in Iceland

But, on a practical level, both the United Kingdom and the European Union’s overall net-zero transitions require far more effective mechanisms to unlock investment.

In short, industry and investors need a business case: one supported both by demand for green products and services, and targeted interventions to stimulate investment. BE is supporting Europe’s journey to become a climate tech leader and meet its ambitious climate goals in a number of ways.

From left to right: Ramya Swaminathan (CEO, Malta), Ann Mettler (BE VP, Europe), Fatih Birol (IEA Executive Director), Bill Gates (BE Founder), and Ursula von der Leyen (President of the European Commission)

In these regions, we’re focusing on key roadblocks to scaling up promising technologies, like long-duration energy storage (LDES) and green steel. We’re also bringing attention to regulatory bottlenecks and slow permitting; forging partnerships, including with the European Commission, the European Investment Bank and the UK government; and addressing key scaling challenges, such as with LDES and e-fuels.

We’re also working to reduce overall transition costs in an era of high inflation by leveraging private finance, tapping into institutional investors’ capital, and working to increase the availability of public risk capital for emerging climate technologies.

It remains important to work across all fronts, because progress is never linear. The Ukraine war and subsequent energy crisis have slowed progress on electrification, which remains the cheapest decarbonization pathway in Europe — just one example of why, even in a region with exemplary climate leadership, it’s crucial to constantly evaluate and adjust our strategies.

Cross-cutting

Low & Middle-

Income Nations

3

3

The key problem with getting the green premium on promising new technologies to zero is that initial production, with a new process and high learning curve, is often expensive, as evidenced by precedents like solar power and lithium batteries. So countries in a position to lower that either through procurement policies or tax credits, can send a helpful market signal for the rest of the world.

Wind turbines overlooking a rural road

Once we have the kind of better-performing alternatives incubated by organizations including Breakthrough Energy, our goal is to help roll out those products at scale — making them affordable enough to deploy in such large, middle-income countries as India and Brazil, and allowing millions, if not billions , of people to reduce emissions while still improving their quality of life. We rely on our evolving global network to make this happen, constantly expanding partnerships with philanthropic actors, lawmakers, advocates, and activists.

One common type of policy hurdle around the world is bureaucratic. For instance, emerging technologies in methane-reduced feed for cows have huge potential to decrease emissions.

But across countries with the biggest cattle inventory, it’s harder to get new kinds of food approved for animals than for humans, which makes it nearly impossible to scale these technologies. We are working globally to solve such policy obstacles, taking into account country-specific challenges and concerns at every step.

Next Steps